La Terre en suspens solo exhibition.

OBORO. Salle Daniel-Dion et Su Schnee et petite galerie.

4001 Berri, local 301, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

April 15 to May 20, 2023.

Opening on Saturday, April 15, 2023, at 5 PM.

Artist Talk on Saturday, May 6, 2023, at 2 PM.

The Matter of Time

Exhibition essay by Ariane Koek

It’s a millisecond versus a billion years. Technological time versus geological time. Currently our world appears to be locked in a deadly war between two different versions of linear time. Elements, such as rare earth elements, which are contained in minerals, have been harboured in the earth for billions of years, and are being extracted with increasing rapidity to power our technology. Deep time transformed into quick time. We are consuming these rocks and minerals far faster than they can re-form. We are literally dematerializing the planet — and as we do so, we are running out of time.

It is these critical paradoxes that are at the centre of the work of François Quévillon. Ever since his residency at Gros Morne National Park in 2017, he has focused on rocks and minerals. His work over twenty years has always been an investigation into the nature of materiality — whether liquid, gas or solid matter. But for the past six, he has found a new focus with geology, which combines the environmental, societal and ethical issues that are close to his heart. His work does not preach about these issues. Instead, it subtly raises questions in the audience’s mind by luring them in with the beauty and skill of his image-making and his creative use of technology.

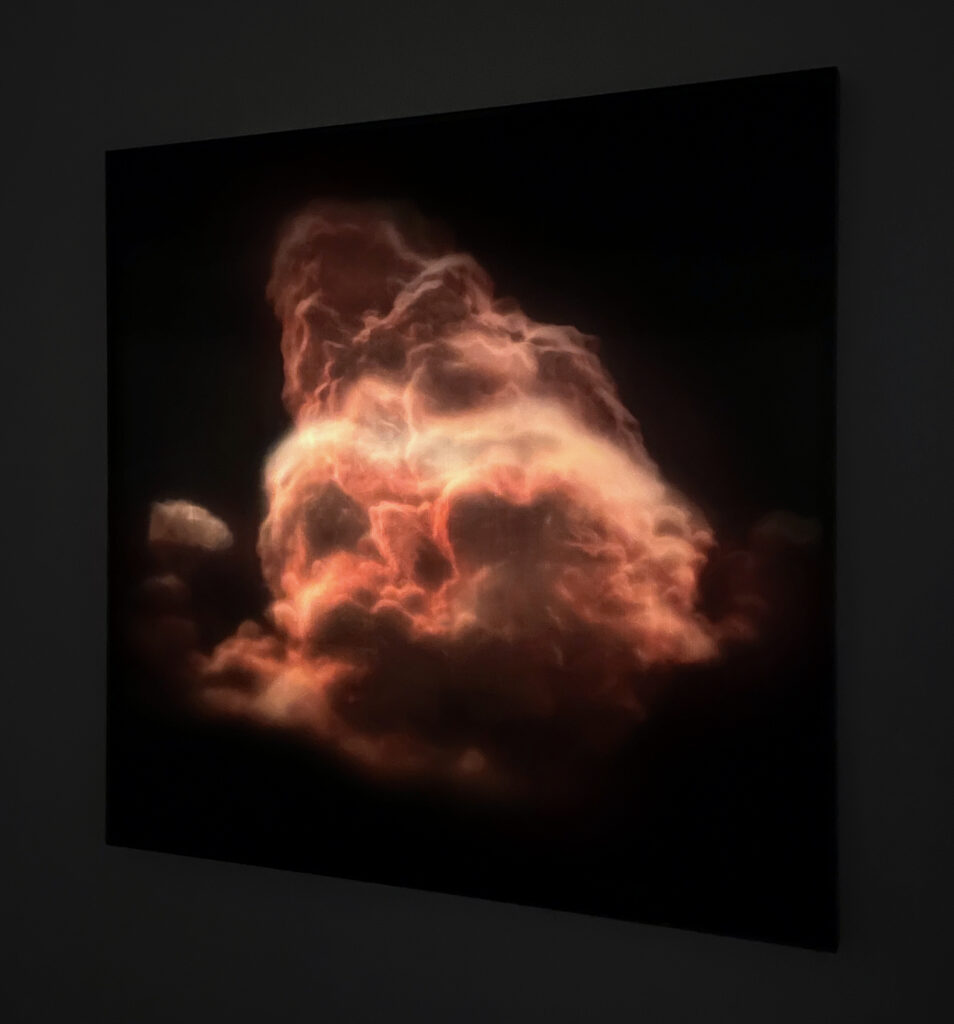

Key to this is his work possessing an unsettling and uncanny quality, too: his images walk the line between the heimlich and the unheimlich — the familiar and the strange1 — and so his work has a beguiling liminality. Take for example the lenticular print Pyrocumulus. As visitors move around, it changes shapes, forms and textures. Molten matter appears to momentarily transform into a volcanic ash cloud, blooming like a flower.2 Or take Cryptocristallin, which could be a blown-up image of a microorganism under the microscope. It’s in fact the interior of a geode rendered with depth of field.3 The accompanying hissing soundtrack, drawn from volcanic activity, evokes the energy needed to form the rock, giving it a life that breaks down the distinction between dead and living matter.

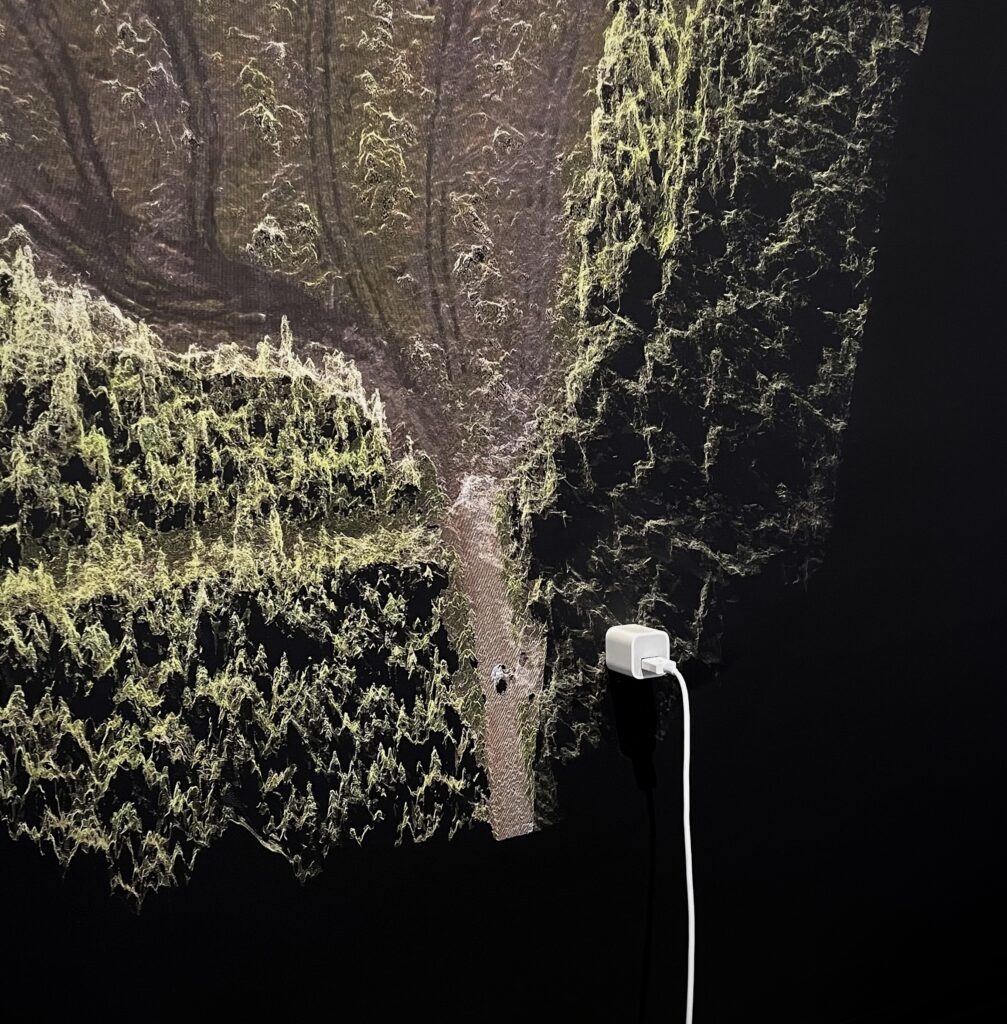

His installation Esker / lithium has an even more complex liminality, partly due to the depth of his research over several years. A haunting 3D scan on a wall appears at first glance to be an unusual natural forest clearing. The clue that there is more to this than meets the eye is the mobile phone connected to the image by an electric cable, like an umbilical cord. The clearing is in fact on a prospection site for the extraction of lithium, which the phone depends on for power. The phone, which is faulty and frequently runs out of power, in turn rests on the image of a mining exploration hole, supported by a pallet of plastic bottles containing spring water collected nearby — a subtle comment on extractivism and consumerism.

The subliminal questions raised by these juxtapositions trigger what François calls “reflective discomfort.” He is deliberately trying to provoke this feeling in his work, and it is a discomfort that he feels, too, because he is using new technology to research, create and exhibit his work, which is also contributing to the extraction and destruction of the planet’s geology. He is just as much implicated in what is happening in our world as we all are. But equally, he is fascinated by the creative possibilities technology offers both him and the viewer, opening our perceptions to new experiences and understandings of our world.

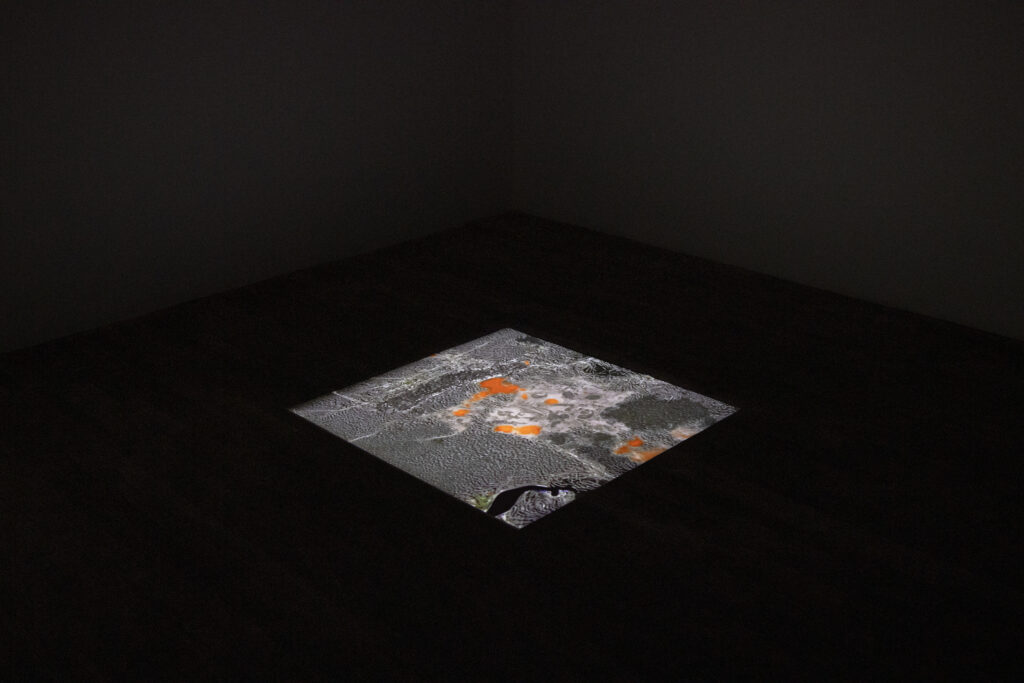

Érosions 3 is another piece with many layers to it. Put on the VR headset, and the rocks which François scanned on the coasts of the St. Lawrence are transformed into undulating waves of particles of light and colour. The boundary between the shoreline and water are eroded, and the work evokes a new geological materiality beyond human perception — the “vital materialism” which the philosopher Jane Benett talks about, where all matter is a form of life, whether it is unconscious or not.4 Technology gives us a portal into seeing rocks as mobile and flexible in this digital realm. Yet in real life, rocks move, and their movement is at the centre of their ‘being-ness’ as any geologist will confirm: they form, reform, and transform over time, and are masters of metamorphosis. They just do this in time stretched over thousands and millions of years, which are far beyond human beings’ bodily experiences of time. In fact, rocks are immortal, except for attrition by weather and the elements, as well as their destruction by humans. Maybe part of our fascination — as well as disregard — for rocks is an unconscious jealousy at their immortality. We are literally destroying them in order to live on borrowed (deep) time.

Érosions 3 can also be read as a critique of the world as solipsistic. When a person enters the room and puts on the VR headset, unbeknownst to them they both trigger sound and images that other visitors in the room encounter. The headset wearer can neither hear nor see what is happening outside their own experience. They are at the centre of their own universe — true members of the Anthropocene.

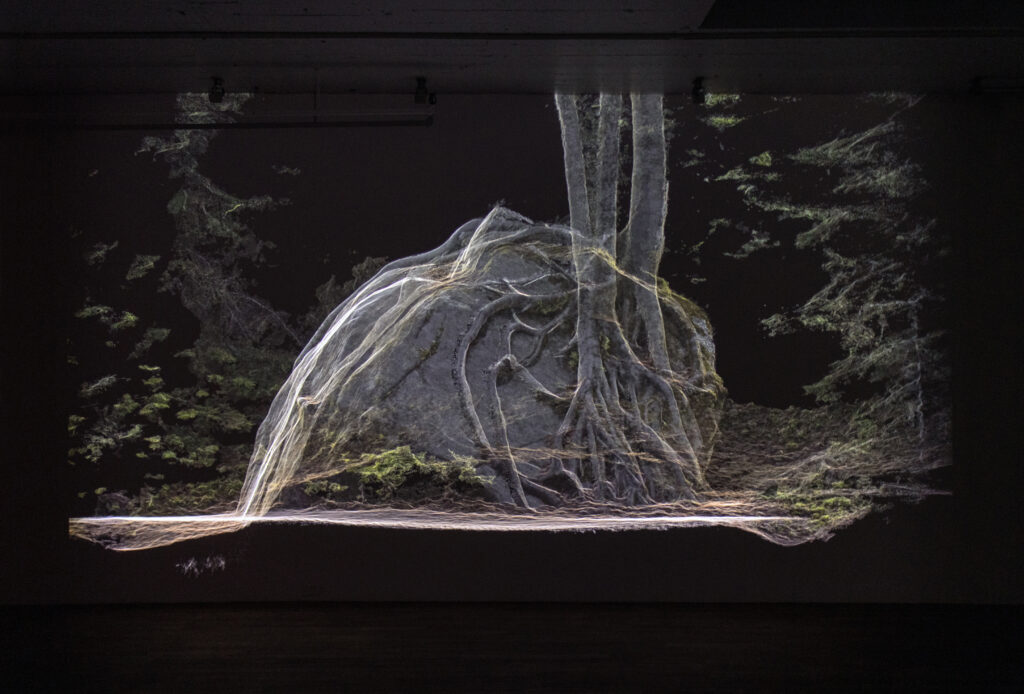

But there is hope, too, in François’s work. Rooting: Le Rocher shows roots gripping tenaciously to rocks with such vigor that it is almost palpable. Life will always find a way. In his book The Order of Time, physicist Carlo Rovelli sets a riddle to test the nature of reality. He posits that a stone and a kiss are in fact the same. They are both an event held together by time:

The hardest stone in the light of what we have learned from chemistry, from physics, from mineralogy, from geology, from psychology, is in reality a complex vibration of quantum fields, a momentary interaction of forces, a process that for a brief moment manages to keep its shape, to hold itself in equilibrium before disintegrating again into dust.5

In the end, François’ work — which investigates the geology of media and the media of geology with their different materialities — hints at this: a state of existence which is even beyond that of the vital materialists for whom everything exists as equals. Instead, as Carlo Rovelli shows, what really matters at the end of the day is time — and the forces that interact and give shape to both a stone and a kiss. Time matters. Time is a form of mattering — of making meaning and shaping the world/s in which all beings exist. We are time.

– Ariane Koek

- See Sigmund Freud’s essay The Uncanny (1919).

- The title Pyrocumulus refers to fire clouds formed when warm air rises. The piece also evokes

Chinese myths which link clouds with rocks — seeing them as the same things, an expression of

matter, despite one being aerosol and the other solid. See Paul Prudence, The Lithic Imaginary

(Sternberg Press, 2023). - The title of the work teasingly and deliberately also evokes crypto art and NFTs — a form that François has not worked with so far.

- Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2010).

- Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time (Penguin Riverhead Books, 2018), p. 62.

This essay was originally commissioned by OBORO on the occasion of François Quévillon’s exhibition La Terre en suspens, presented from April 15 to May 20, 2023.

La Terre en suspens is inspired by geology in order to probe the space-time and materiality of the digital. Mainly composed of digitized rock formations and fragments of territories altered by algorithms, the works echo the implications and effects of certain technologies on perception, while offering new perspectives on the evolution of the Earth, its composition and the processes that impact it, such as erosion, volcanism, as well as the extraction and transformation of minerals in a context marked by globalization and climate change.

This exhibition is the result of several residencies in Quebec and elsewhere in the world. During his stays, François Quévillon conducted fieldwork and met with communities to examine local environmental particularities and concerns. The extraction of tezontle from extinct volcanoes south of Mexico City; the importation and residue of bauxite from the aluminum industry in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region; lithium mining, water and the forest in Abitibi-Témiscaminque; and the St. Lawrence coastline are among the subjects addressed. As a result, the diversity of the devices presented questions our relationship to screens, reminds us of the mineral nature of their components and the resources required by the digital and energy transition.

François Quévillon would like to thank the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Canada Council for the Arts and the organizations that participated in the research and production processes of the works, notably during residencies: Parks Canada, The Rooms, CQAM/Turbulent, Bang, Connecting the Dots, Instituto de Geografía (UNAM), Est-Nord-Est and Molior. He also thanks Etienne Richan, Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit, Nancy Lombart, Ariane Koek, Carmen Salas, Eric Mattson and the entire OBORO team.